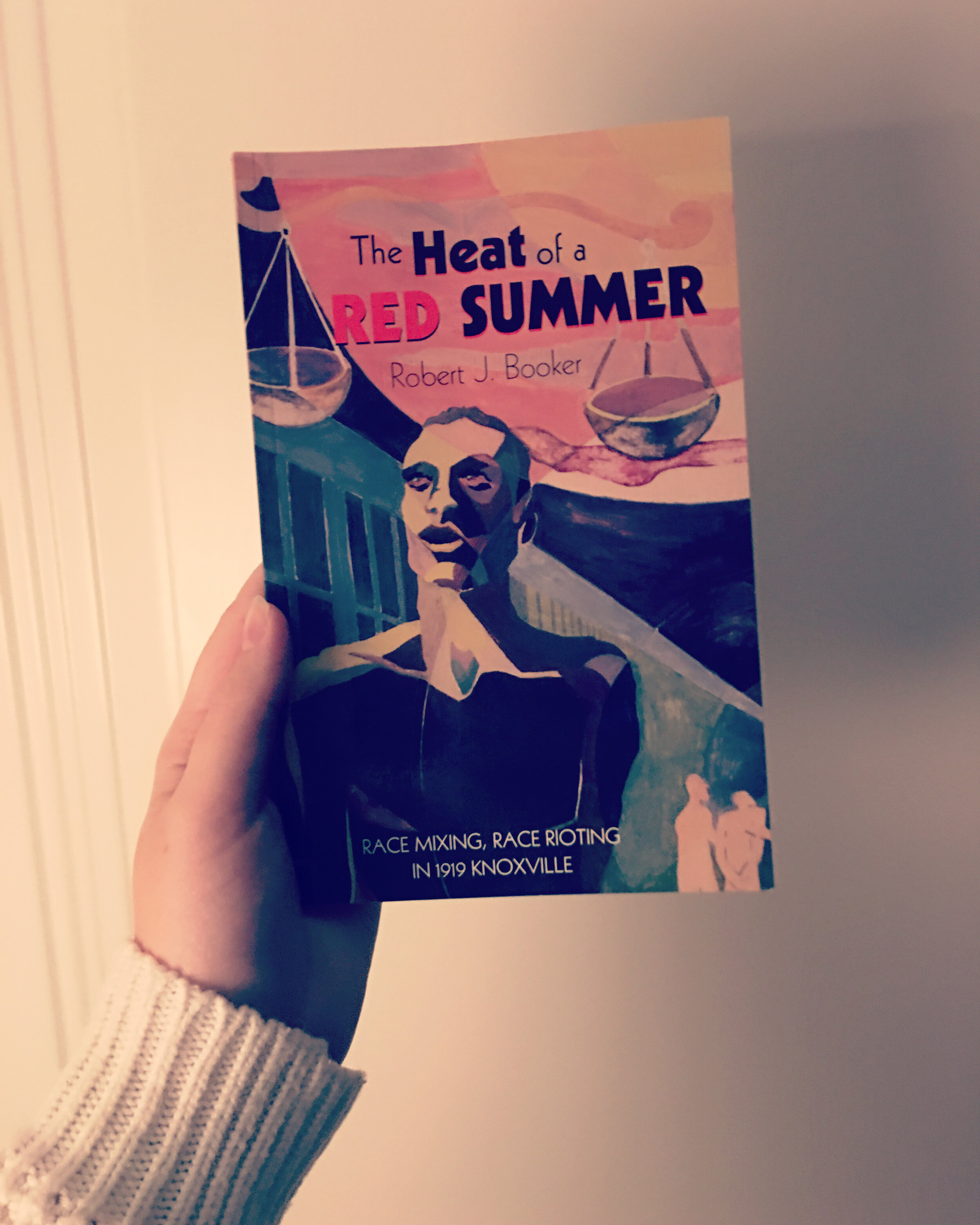

Commentary: The Heat of a Red Summer: Race Mixing, Race Rioting in 1919 Knoxville by Robert J. Booker

Lauralei’s Instagram @rebelmouthedbooks: https://www.instagram.com/p/B4fd0Vtgfjf/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

Knoxville, Tennessee 1919:

World War I has just ended. For Black veterans, returning to Jim Crow brought with it pain and bitterness. Tensions blistered as Black veterans clashed against segregation and white people eager for a return to "normalcy." With summer came the oppressive heat and humidity known to Appalachia, and in its wake, came a series of attacks on White women by an unknown perpetrator. For a relatively liberal southern city like Knoxville, where a strong Black business community thrived and Black men had been elected to public offices, officials were eagerly looking for ways to calm the public's unusual uproar. They found their scapegoat for it all in a young Black man named Maurice Hayes. His arrest and false conviction for the murder of a White woman stirred locals to a fever pitch and a White mob stormed the Knoxville jail and then rioted in what was then referred to as "Little Harlem," the Black business district. The term "Red Summer," coined by James Weldon Johnson, who was a prominent leader of the NAACP, was so named after the violent nature of the riots that ripped through many cities in the U.S that year-- targeting Black communities.

He stressed that the "injustices and harassment were not only the tools of mobs, but of local, state, and federal officials as well."

I grew up in Knoxville. It's the third-largest city in Tennessee, located in the Eastern part of the state, nestled at the foot of the Great Smoky Mountains. I've been far from home for a while now, but when I visit, I remember everything again. I remember the streets. I remember who lived where and when. I remember the route I walked home from elementary school. I remember which parking lots are safe to sit in by yourself-- if you need a moment to think or nap. I remember the creek that ran behind my high school and the trail famous for teens who wanted to smoke in privacy. I remember when dead bodies were discovered there too. I remember where the public bathrooms are and which Panera Bread bathroom I could use without paying for food. I remember how to walk to the public libraries, and which unmarked side streets are quickest.

I remember where my cats were each discovered-- strays finding homes. I remember performing with my dance company in pretty much every public spot in town. I remember the high schools and their mascots, though I maybe attended two HS football games total. I remember which of my teachers were racist. I remember the hidden passageways in my childhood church and how dark it got when no one else was around. I remember which neighborhoods were the prime Trick-or-Treating spots. I remember how to navigate the clusterfuck of downtown Knoxville on a UT college football day. I remember which months mark the end of summer and the beginning of winter. I remember the sounds of cicadas in the trees. And I remember what it was like to call Knoxville home.

Each of us has memories like these about the places we grew up in. Good and bad. Fun and terrifying. Playful and malicious. I have seen both sides of Knoxville. But one side I had not seen was Knoxville's history with race. It isn't taught in many schools. It isn't discussed in public very often. But because of people like Robert J. Booker, because of his works like The Heat of a Red Summer, and because of places like the Beck Cultural Exchange Center, centering African American History and Culture, this side of Knoxville's history is written and shared.

Booker's 105-page book on Knoxville's 1919 Race Riots is a vital necessity for anyone who has ever called Knoxville home. Booker's in-depth research explores the physical landscape of Knoxville at the time and how Black people navigated those spaces for work, pleasure, and community. Through Maurice Hayes' life, we gather an image of what it meant to be Black and live in Knoxville in this era. We learn the names of Knoxville's Black business owners, elected officials, and community leaders. We learn the names of the wealthy, White families who float in and out of Maurice's life for the good and the bad. We read excerpts from the Knoxville papers of the day and what they had to say about the Black members of their town.

Knoxville folks, like myself, tend to think highly of Knoxville. It was sympathetic to the Union cause during the Civil War, it urged Black people to vote and hold elected office shortly after slavery ended, and it is one of the few southern cities that had Black police officers during Reconstruction. Knoxville, compared to its neighbors, sees itself as more liberal, more welcoming, more inclusive. But few of us have really taken the time to look back in history to learn the full story.

The full story is that Knoxville is and has been racist towards its Black communities. We can all pat ourselves on the back for the fact that Knoxville wasn't as violent as other places, but such congratulations only serve the White population. As this book showed, Knoxville's history with race and racism perfectly captures the essence of the White progressive movement: We're not perfect, but we're better than those guys over there *points to Alabama, points to Georgia, points to South Carolina*.

This mantra isn't enough for real change. It's the first step, sure. But we can't stop there. Knoxville, like many U.S cities, has to take the time to unpack its full history and truly evaluate how far it has come in the last 100 years. Based on what I read in Booker's The Heat of a Red Summer, we haven't come far enough.

Just like in 1919, Knoxville tolerates Black presence and existence. It occasionally celebrates exceptionalism. It is quick to point out the Black community's flaws without taking ownership of the White community's part to play in it. When something goes wrong, it finds its scapegoats in Black people. It seeks justice but only for White people. These themes are what create the story Booker tells us in The Heat of a Red Summer and they are still alive and well today.

So what's new today? Well, Knoxville has jumped on the gentrification train, pushing Black and Brown communities out of their neighborhoods to make room for breweries and coffee shops. Rent is going up and historic Black neighborhoods are threatened. Segregation isn't dead.

Knoxville has a lot of work to do.

There are so many things I love about Knoxville. The people there really do care about one another. You can feel that love when a woman you haven't seen since 6th grade bumps into you in Kroger's and asks you how your brother is doing. You can feel that love when strangers in the Downtown Farmer's Market stop you to share a tip on where to park that morning without having to pay too much. You can feel that love when school teachers you never had yourself take the time to tell you how much they loved teaching your best friend. You can feel that love when someone is sick and the entire neighborhood gets together to cook for them or drive them to the doctor. You can feel that love because Knoxville is full of genuinely amazing people.

I say all of this because Knoxville is my hometown and there is a lot to be proud of. But, at the same time, Knoxville is my hometown and I'll never go easy on it-- especially when there is still so much work to do to confront our racist past and our racist present.

For those of you who live in Knoxville, I urge you to buy this book, read it, and talk about it with those you know. If you're a teacher, find ways to incorporate this history into your classes. If you're a public official, make sure you don't repeat this history. If you're a business owner, see about stocking this book and others like it on your shelves or talk to other business owners who might be interested. Buy Black and stand in solidarity with Knoxville’s Black community.