What 2018's Most Popular Reads Can Teach Us About Writing Successful First Chapters

What makes a great first chapter of a book?

Writers know that creating a successful first chapter is truly a feat worth celebrating. It’s hard to navigate the “rules” as well as your own voice.

But, before I dive in, I’d like to make a recommendation for writers reading this: If you are a writer just now beginning your first draft, don’t listen to a word I say. Write the first draft. Go with your gut. Do what feels right. Only after your first draft is behind you, should you return to outside resources. This is just my recommendation. I remember when I was getting my story out the very first time, and I was drowning in resources telling me the millions of ways to do this right, and it was bewildering. Because I was bending myself to fit within each rule of writing, I couldn’t hear my own voice through the noise. So give yourself the time to listen to what is already inside you before trying to absorb the resources around you. We can chat once your first draft is on paper.

So how can we decide what makes a good first chapter?

The truth is that the best first chapters succeed for different reasons. It all hinges on the kind of story you want to tell. There is no all-encompassing template that makes a perfect first chapter for everyone’s story. (And, if you find one online that claims to be so, think twice about using it to create your first chapter. You may abide by all the “rules” and still have a boring, predictable first chapter at the end of it.)

But Lauralei, that’s not helpful.

You’re right.

That’s why I’ve decided to participate in an exercise: Let’s break down the structure of first chapters belonging to some of 2018’s most popular books to see what knowledge we can harvest.

I have selected these titles from 2018 to study in this post:

There There by Tommy Orange. Literary Fiction.

Children of Blood and Bone by Tomi Adeyemi. Fantasy.

Educated by Tara Westover. Memoir.

Neverworld Wake by Marisha Pessl. Young Adult + Mystery.

Why did I select these books? Because they’re popular. They won awards. They sold well. They got publishers excited. They got readers excited. If you read these texts and didn’t like them, please don’t give up on this post. This is not a review. This is an exploration. This is a chance to learn from successful books. I’m not trying to say that commercial success means the book is flawless. I am trying to say that when a book sells at the rate these do and did, then there are undoubtedly things to learn from them.

In case you don’t have time to read this entire post, here are the lessons I’ve pulled from these first chapters:

Set expectations in your first chapter.

If your story is one stemming from survival, use your words and style to spark debate and maybe even discomfort.

Don’t be afraid to wear your heart on your sleeve.

Write what you love.

To combat passivity, you must challenge the way you explore and re-tell memories.

Follow the needs of your character, even if it makes people question your use of space.

The physics of reality can and should be shaped to fit your story and your commentary on the world.

The lessons themselves; however, are only half the value of this post. The full length discussions raise important questions and ideas that all writers can benefit from. I hope you take the time to read more.

Now, let’s talk about the Six structural terms I’ll be using throughout the blog.

Writers and readers alike get scared when they see the word “structure.” It’s daunting because it feels especially academic, clinical, and boring. But structure doesn’t have to be any of those things. Honestly, we could simplify the conversation a lot by first addressing that most of us respond to structure on a gut-level much more than on an intellectual one. We can tell when something with the structure is "off" without breaking it down piece by piece. Something is wrong with the pace. The characters don't stick their landings. The world isn't believable. All of these complaints touch on structure, in one way or another. And these complaints can make or break a story. If, we as writers, challenge our understanding of structure, then we will be better able in the future to pinpoint the roots of those problems in our writing.

My main resource for this material is Sandra Scofield's book The Last Draft: A Novelist’s Guide to Revision. One of her recommended exercises asks readers to select a chapter or passage from a book they enjoy and break down the structure based on six basic terms (explained below.) I am replicating that exercise here.

I repeat: This is an exercise. I’m repeating this because I know there are academics, writers, educators, and readers out there who would argue that my methodology here does not cover the full range of “structure.” I recognize that. This is not a treatise on what structure is in its entirety. This, rather, is a first step for myself in exploring what structure looks like and feels like on the page, particularly in first chapters. I am exploring structure through this lens in the hopes of discovering patterns or overcoming preconceived ideas so that I can be a better reader and a better writer. In this endeavor, I hope my fellow readers and writers join me and discover new things for themselves.

When telling a story, any sort of story, you are going to have these six elements. I try to visualize these elements as features of a house (see my poorly drawn illustrated to the right,) so that I am better able to remember their functions in storytelling.

1. Scenes, the individual rooms inside a house: Readers and writers alike sometimes struggle with the nature of scenes. We know what the word means, but we don't always know how to recognize it on the page. Where a scene begins. Where it ends. If it helps you, picture scenes as rooms of a house. You know when you enter a room. You know when you exit. When you are in the room, you know why it is there. The kitchen is there to cook in. The bedroom is to sleep in. The living room is to gather in. And so on. Sometimes scenes are just one room, and sometimes they are like an open concept floor plan-- they sprawl out and one room takes on several different names. Scenes can do this too. Sometimes scenes are just one room, just one situation, and sometimes a scene can take on several situations at once. It's all about what the story is trying to get across. Scofield recommends testing scenes by turning them into a statement: What Happened + What Did the Characters Feel? = How the Scene Progressed the Story Overall. Scenes, like rooms, house action. This is how they move the plot forward.

2. Scene Fragments AKA Moments, the closets/crawlspaces inside a house: Scofield and pretty much everyone else uses the term "Scene Fragment," but I don't like that term; I prefer “moment.” Scene fragments are not full scenes. They are flashes of memory or reflections or tangents. They can occur on their own or within larger scenes. The word "Moment" over "fragment" gives the writer room to stretch their legs and explore, without feeling that somehow it is less important. To me, moments are just as important as scenes. Memories are a part of what make us real people. Our characters have memories, and writers should make that clear to readers when it can add meaning, tension, suspense, or beauty to the larger story. I think of moments as closets or crawlspaces, because we go into those spaces looking for something-- a coat, old photos that we hide in shoe boxes, Christmas decorations. When a writer places a moment within the text, they are letting the readers look for something within the story world. Imagine a character in a book opens a closet in their apartment and they stumble across one of their childhood toys. In that toy, they remember that it had been a gift from their father, who has since passed away. This moment gives the reader permission to look for something new about the character or their world. Do they miss their father? Or do they want to forget about him? What role did the father play in the world where the character lives? Maybe he built the house we are wandering right now. Maybe he put a curse on the house. All is possible within such moments. But writers must use them expertly, or else they could disorient the reader and confuse them. Done well; however, moments can make a story bold and fresh and, above all, real.

3. Narrative Summary, the hallways and staircases of a house: We need Narrative Summary to get us from Point A to Point B without wandering through every room in the house. Basically, Narrative Summary is when the writer compresses information into an interesting, touching, meaningful passageway. And it should do it economically, making the information more digestible, without taking up too much room on the page. Take us from the living room to the kitchen, without dragging us through the foyer and the dining room too. Imagine a hallway that leads from the living room to the kitchen. What's hanging on the walls of the hallway? Maybe family photos or framed diplomas. As you walk this hallway, you learn a bit about who is in the next room. You learn who occupies the house with you. They are the youngest of five siblings. They studied Architecture. They used to have braces. Narrative Summary can contain all sorts of information: setting, a passing of time, character developments, etc. But, beneath the information, Narrative Summary MUST get the reader excited to dive into the scene or the world. While "summary" may make it sound dull, Narrative Summary should be the opposite. It should convey a mood about a place or time.

4. Interiority, the shower: That may sound like a weird analogy, but hear me out. The purpose of interiority is to connect the reader with the characters and their world more deeply. Interiority gives readers perspective. You know how when you’re in the shower you have the best ideas? In the shower, you can process all the information of the day, you can daydream, you can reflect on something that is bothering you. This is interiority. Normally, interiority is not necessary to the plot. It isn't like narrative summary, where information is needed to push the story along. It can, but normally, it’s there to develop characters so that they feel real— grounded in their existence. Interiority includes all of the following:

a. Response: How a character reacts to something. Let’s say your character in in the shower. What made them get in? Maybe they were cooking in the kitchen and they spilled the sauce they were making all over themselves. They tantrum and decide to give up on dinner altogether. Your character gets in the shower to clean off.

b. Reflection: How a character thinks about something. Maybe after the character gives up on dinner in anger, they reflect on why they reacted that way. "That was a childish reaction," they may think to themselves. "It reminds me of when I was a little kid and I'd get frustrated by things too easily and throw a tantrum."

c. Interrogation: How a character explores or challenges something. After the character reflects on their tantrum-like behavior, they may ask themselves, "Why am I like that?" Is it because their mother wasn't around a lot and so throwing tantrums was an easy way to get her attention? If so, what does that say about their maturity as an adult? Maybe the character is recently engaged, and, after this tantrum, they wonder if they are ready for marriage.

d. Commentary: A message that the character or narrator wants to share about something. After reflecting and interrogating, maybe the character decides that we all have childish sides to us, and we have to grapple with them if we want to enjoy the benefits of growing up: freedom, marriage, sex, etc. The character gets out of the shower and moves on with their day, but now we know some new information about them: they have a temper, their mother is a sensitive area for them, and they’re questioning their readiness for marriage. That’s a lot of important context to give to your reader about your character. Interiority supplies pieces of information just like this.

5. Foreground vs Backstory, the house of today and house of yesterday: Foreground and Backstory are very simple concepts to see on the page. Foreground is what is happening "now," while Backstory is what happened "before." How much time writers spend in the present and the past tells the reader what the story is "about." Foreground is the house as it is today: whether or not it is fully constructed and everything that is currently happening in the house. Is the owner fighting with their daughter that lives upstairs? Does the dog bark at passing traffic? Is a radio playing? Backstory is like what used to be on that land before the house was ever there. Was it an open field? If so, was it a part of farmland? Or was there another house there? Did the owners pass away? Did they sell the land so they could sail in the Bahamas? Or maybe the Backstory is the history of the house itself-- when was it originally built? Who built it? These story lines weave together throughout the story to paint a vibrant picture. Foreground and Backstory frequently mesh together to help the reader feel that their feet are firmly planted in the soil of the story.

6. Action, what is happening inside the house: Action is exactly as it sounds. When something happens it is called action. Action touches on all the other terms I’ve described. Action occurs within a scene, pushing the plot. Action can be summarized by Narrative Summary. Interiority is a reaction to some sort of action. Action occurs in both the Foreground and Backstory. Action progresses plot. Action heightens or lowers tension. Action forces characters to make choices. Action makes the reader read faster; it builds excitement. Action is what’s going on inside our metaphorical house. Did one of the kids running around inside just break a vase? Did someone just clog the toilet upstairs? Did an angry neighbor just break one of the windows? Did Grandma just shout down at one of the kids to bring up her cigarettes, which then set off the smoke alarm? All of these things involve action; they require verbs. Something happened that changed the house; it changed the story.

Let me briefly explain the structure of this blog post:

For each book, I will first share three things:

Links to reviews so that if you have not read these texts, you have resources at your fingertips to learn more.

A statistical breakdown of the structural components present in the first chapter of each book. (See left for key.)

A chapter tagline giving a 1-2 sentence description of what happens in the chapter.

Now, I know numbers imply accuracy and precision, but I’m here to admit now that they will not be scientifically 100% accurate, because we are dealing with art. The numbers are just an attempt on my part to paint a picture of how much of each component I saw in the first chapter. When reading, these structural terms blend together, sometimes within the same sentence. That’s what makes it art. The individual pieces blur together to create a sensation for the reader. So, while you will see I try to create stats for each book I study here, I advise you to focus more on what I write based on those stats, not the stats alone.

As for the chapter taglines, I am employing an exercise that I discovered again in Sandra Scofield’s The Last Draft. She writes, “Go chapter by chapter and say what happens. In a sentence or two. No details, just what it adds up to.” I find this useful when discussing structure, because each chapter of a book should, hypothetically, progress your plot. By writing a tagline of what happens in a chapter, we clearly see an end result of whatever structural choices the writer made and we can discern how successful the chapter is.

Now, let’s dive in!

There, There by Tommy Orange. Literary Fiction.

To learn more about this text, if you have not read it, check out NPR’s review here. Or if you would like to see a review by someone who did not like this book (2 out of 5 stars), check out Rod Kelly Hines’ Goodreads here.

Chapter 1 Number of Pages: 12

Number of Scenes: 6

Number of “Moments”: 8

Number of Lines of Narrative Summary: 136/313

Number of Lines of Interiority: 136/313

Number of Lines of Foreground: 34/313

Number of Lines of Background: 213/313

Number of Lines of Action: 44/313

Chapter Tagline: Tony Loneman and his friend, Octavio, make a plan to rob a powwow in Oakland, CA.

There There was the first book I read for this exercise and it was an excellent way for me to begin, because it proved to me right off the bat that structure may sound like a science, but it is just as much a personal perspective as anything else in art.

There were plenty of moments for me, while studying the first chapter of There There, when I thought I was doing something wrong. I'd read a sentence, think about it, and decide it was one thing. Then the next moment, when I'd go back and read the previous sentence over again, I'd think, "Oh, no. That's not right. That's summary not interiority." Or something like that.

I got frustrated. Not at the writing, but at myself. What wasn't I getting?

I re-read Sandra Scofield's exploration on structure in The Last Draft. I tried to pinpoint where in reality I was messing up. Then I realized that it wasn't me messing up. I was frustrated because I was trying to force structure as a scientific concept onto a piece of art. So I stopped trying to force it. I accepted that I would "mess up," or analyze a sentence a certain way one moment and then it would change for me the next. Even after 20 reads-- the meaning would change.

And that's okay. Because this book, to me at least, is a lot about reflection. About remembering. About taking what was and negotiating with what is. About how things change or don’t change. The book’s structure boldly owns this.

As you saw from my stats, There There’s first chapter is structurally dominated by Backstory, Interiority, and Narrative Summary (see right.) This structure gives the first chapter an interior-ness and a sense of wandering that some readers really don’t like. But, for the story Orange is trying to tell, the reflection and commentary are key. This is a coarse, harsh text, but with large swaths where there is no action. Sometimes, when a story has little action, it is because the writer is focusing more on character development. But I’ve seen many readers complain that they had a hard time connecting with Orange’s characters on an emotional level. But I don’t think this is because there is poor character development. I think this more has to do with the fact that most, if not all, of the characters have really hard lives that makes people uncomfortable. But discomfort is important.

Interiority includes commentary— characters taking stock of their reflections and making statements about how their world works or should work. And, as you can see from the stats, interiority represents the majority of this first chapter. And this book is mostly commentary.

So there is lesson one: Set expectations in your first chapter.

Then follow them. Or don’t follow them. But whatever you choose, make it intentional. Expectations, I have found, can make or break a book. So be honest with yourself and your readers from chapter one.

Furthermore, the first chapter of There There is mostly made up of scene fragments, or “moments.” The scenes that are present are short. This gives sometimes for a choppy read. It feels like an off-trail hike. Sometimes you find a clearing where it is easy to walk, but other times you have to scale boulders. Sometimes, this style can make readers uncomfortable, because it doesn’t abide by the general rule that stories are made up of clear, tight scenes. But Orange’s structural choice here connects with the message of the story as a whole.

There There is the story of what Orange calls “Urban Indians,” or Native people who inhabit America’s cities. The message here is that Native people don’t just exist in “nature” as many white people fantasize, AND that Urban Indians are no more or less Native than those who live in other places. They are not a dead or extinct people; they are alive today, facing today’s expectations and needs, inhabiting current spaces in the real world. Orange’s stories in There There explore daily experiences for Native people living in Oakland, CA, all intersecting, by the book’s end, at a powwow. The scene fragments or “moments” within those day-to-day experiences allow the reader a glimpse into context— why and how those experiences are the way they are.

Recently, I read a book called Spider Woman’s Granddaughters: Traditional Tales and Contemporary Writing by Native American Women by Paula Gunn Allen. In that text, Allen discusses Native American literature compared to Western literature’s standards of excellence, and how Native American writings have been historically viewed as lesser than, because they do not adhere to western storytelling rules and regulations. Allen writes,

“Native writers write out of tribal traditions and into them… what has been experienced over the ages mystically and communally — with individual experiences fitting within that overarching pattern— forms the basis for tribal aesthetics and therefore of tribal literatures. Native novels, whether traditional or “modern,” operate in accordance with aesthetic assumptions and employ narrative structures that differ from western ones.”

She mentions that most “white Anglo-Saxon secular-protestant” stories hold certain ideas and traits as morally righteous and therefore profitable for literature, like individualism and conflict centered around one person’s journey towards a goal.

She continues, “But the Indian ethos is neither individualistic nor conflict-centered, and the unifying structures that make the oral tradition coherent are less a matter of character, time, and setting than the coherence of common understanding derived from the ritual tradition that members of a tribal unit share.”

She concludes, beautifully, that, “The Native literary tradition is dynamic; it changes as our circumstances change. It pertains to the daily life of the people, as that life reflects, refracts the light of the spiritual traditions within which we have our collective life and significance.”

As Paula Gunn Allen wrote, I see Orange’s structural choice of employing scene fragments, or “moments” more often than the western-idealized “scene” as a method of capturing daily experiences plays an interesting role in this kind of discussion on storytelling aesthetics.

This brings us to the second lesson we can learn from There There’s first chapter: If your story is one stemming from survival, use your words and style to spark debate and maybe even discomfort.

Readers will react, and maybe a few will try to fit their reading experience into a larger context that will open their eyes to structures of literary criticism in place. If this idea is one that excites you, then go for it. But if this is not the kind of story you want to tell, don’t. It is entirely up to you.

All told, There There employs backstory, interiority, and scene fragmentation or “moments” to create a storytelling style that sets expectations for discomfort and unease right from chapter one, while building a coarse connective tissue between characters through their individual daily lives in one of America’s cities, who eventually live a shared traumatic experience at a powwow. If this sounds like something you can learn from, please pick up a copy of this brilliant debut novel.

Children of Blood and Bone by Tomi Adeyemi. Fantasy.

To learn more about this book, if you have not yet read it, check out NPR’s review here.

Chapter 1 Number of Pages: 17

Number of Scenes: 4

Number of “Moments”: 0

Number of Lines of Narrative Summary: 127/510

Number of Lines of Interiority: 217/510

Number of Lines of Foreground: 477/510

Number of Lines of Background: 33/510

Number of Lines of Action: 230/510

Chapter Tagline: Zélie, a young magi who survived the genocidal Raid against her people, trains to fight under the watchful eye of Mama Agba and, after a tense encounter with the royal guard collecting unfair taxes, Zélie graduates Mama Agba’s clandestine program for young girls, before her brother delivers bad news about their father.

Children of Blood and Bone is perhaps the most popular and most widely loved book on my list. Readers are raving. The public is engaged and excited by how the fantasy story tackles our real-world issues, like genocide, colorism, racism, police brutality, violence, etc. Fan artists have produced innumerable illustrations inspired by the magical world of Tomi Adeyemi’s creation. People are in love. And for good reason.

I follow Tomi Adeyemi on Instagram (if you don’t you should,) and she is perpetually passionate about sharing her work with the world. She is connected to her readers, she is open with her process, and she is candid with her emotions— even when she is suffering or anguished. She is young and black and wildly intelligent and inspired. This is the kind of writer young writers need to see out in the world. Why? Because, I (and many of you) have grown up with a specific image of what writers look like and act like. In high school and college, the overwhelming majority of writers I learned about, saw lecture, and was asked to read, were not only white and old, but depressing.

The image celebrated pessimism. It celebrated a distance between writer and reader. It celebrated formality. It celebrated whiteness. It celebrated cleverness over compassion. It celebrated intellectualism over love. To quote Charlie Chaplin’s speech from his film The Great Dictator,

“Our knowledge has made us cynical. Our cleverness hard and unkind. We think too much and feel too little.”

We are taught that our writing must achieve a certain tone to be critically and popularly celebrated. We are shown example after example of literature and short stories that champion the same voice— jaded, cynical, defeated, a bit bored, sarcastic at times, but ultimately forgettable. We were told that, if we write this way, we will become “authors.”

But Tomi Adeyemi proves that doesn’t have to be true.

Here is the first lesson writers can learn from the first chapter of Children of Blood and Bone: Don’t be afraid to Wear your heart on your sleeve.

Children of Blood and Bone has inspired many for all kinds of beautiful reasons. But for me, I am perhaps most inspired by Adeyemi’s example to writers everywhere. Her spirit, her passion, her vulnerability, her liveliness, her realness, all that she is, are a strong reminder that writers don’t have to become the closed-off writer if we don’t want to. We can be fun. We can be exposed. We can be proud of our work. We can cry when we open the first copy of our published book, (which Tomi Adeyemi did on video.) We can love our characters openly, like we would love our children or our friends. We can open ourselves up and let everyone pick through our scars, our tears, our soft spots.

How do we see this structurally on the page?

Adeyemi will frequently combine both an action and a response from the character (interiority) into the same sentence or line. I think this is especially important for this story about a young, black girl’s power in an oppressive system— every action, even subtle, has a consequence or a response. Nothing in the life of these girls gets to just be a sideways glare, or a sharp turn, or a step forward. A sideways glare implies a threat of violence. A sharp turn comes with the moment of fear— a fear of death. A step forward isn’t just a step forward; it is a sexual advance that can have devastating consequences. These actions that, in other books, can just be descriptors of movement, in this text are structured as clear threats. Every movement has implications. Adeyemi’s love for her characters, for her world that she has built, for the story, shines through here. Every line is filled with motion AND reflection. Adeyemi’s writing is firing on all cylinders, because she is passionate, because she is loving and excited. You can feel it structurally, even if you don’t know how or why. It’s there— in every sentence.

And (even though this is not in compliance with the title of this post,) I want to point readers to Adeyemi’s Author’s Note in Children of Blood and Bone. To read the Author’s Note (see left) is to be told point blank that the passion of Adeyemi’s writing comes from just as real of a place in her soul, in her life, in her people’s lives.

I draw your attention to one of her closing lines:

“…let this book be proof to you that we can always do something to fight back.”

You can be both passionate and literary at the same time. If you let your passion come out, you can inspire readers not only to fall in love with your story, but you can also inspire readers to take the message of your tale out into the real world and catalyze change.

It’s easy to hide behind “literary-ness.” It’s easy to craft isolated, detached, too-chill characters and stories. I say it’s easy because it helps the writer feel a bit safer, when sharing that work with the rest of the world. It’s less dangerous because if people shit all over your work when you have distanced yourself by miles and miles of formalities with being a “literary scholar,” then you might not feel the burn and sting of rejection. When you put your whole heart and soul into the writing, when you reveal your personal passions and loves and joys, people’s harsh criticisms hurt even more, because you made yourself vulnerable. It’s scary to be vulnerable. It’s scary to be exposed, knowing the world could turn on you at any minute. But that’s kinda the point. Writing is about exactly that.

B&N Special Edition Annotated Chapter. Tomi Adeyemi’s handwriting can be seen in the margins.

If you are a writer who can admit that you’ve hidden behind “literary-ness” before, but you don’t know how to do differently, this ties into our next lesson.

Here is the second lesson we can learn from the first chapter of Children of Blood and Bone: Write what you love.

The advice you hear a lot is: Write what you know. I think that advice should be revised: Write what you love.

If you are passionate about something, learn more about it and include it in your book. What makes us strongest writers is writing about what we love most. And readers can feel it on the page.

Adeyemi is a perfect example of this.

After graduating with an English Literature degree from Harvard, Adeyemi went on fellowship to Salvador, Brazil, where she studied West African mythology and culture. In her interview with Jimmy Fallon, Adeyemi describes the experience of being in Brazil on a rainy afternoon and being forced into a shop to keep her hair dry. In the shop, she sees a picture of African Gods and Goddesses. And it blows her away.

“I’d never seen anything like that. My imagination had never gone as far as to think there could be Black Gods and Goddesses. And instantly, I saw the world, I saw the giant lions and the jungles— I saw the magic.”

According to Kate Tuttle’s piece in the Boston Globe about Children of Blood and Bone, “Adeyemi built her fictional world from the real language, landscape, and architecture of her ancestors; she named places on her world’s map after her grandparents. ‘It’s based on the culture they gifted to me,’ she [Adeyemi] added. ‘It’s basically my heart in a book.’”

Tomi Adeyemi studied the culture, history, mythology of her people, her ancestors because it called to her. She loved the subject. She wove it into her own story universe and into the fabric of her characters.

In my Special Edition copy of Children of Blood and Bone (see right above), there is an annotated chapter at the end of the book. Adeyemi’s handwriting in the margins of her work sheds light on the things she is exited about as a writer, as the creator of this world.

Here we see pieces of Nigerian culture and things she loves rising up out of the page and into our hands; we can feel their realness, their beauty, their spark.

But how else do we see this on the page within the first chapter?

The first chapter of Children of Blood and Bone is almost entirely foreground and action. The only moments where background comes into play are when the girls are listening to Mama Agba tell the story of their history, giving us, the readers, a lot of important context about the magic and politics of this world.

Just a little over halfway through the chapter, the action subsides and Adeyemi incorporates history into a dialogue between Mama Agba and her students (see left.) This is where we see the foreground morph in with the backstory, and this is also where we find the majority of our Narrative Summary— exposition including important information about the rules and history of this magical world. Adeyemi answers a lot of big questions in this first chapter through the use of Narrative Summary, which is super important if you are writing a Fantasy novel or short story. When you are introducing your readers to a brand new world with its own culture and rules, readers appreciate being given enough information to satisfy certain questions right off the bat. Questions like: Why are these students being trained to fight? Adeyemi answers this in the first chapter. Using Narrative Summary can get to the point of what you are trying to say economically, rather than through intricate plot points or mysterious dialogue. The blending of structural elements together into the same paragraphs, the same lines, even the same sentence is what is so masterful here.

Looking at the annotated page feels like looking at someone’s heart rate when they listen to their favorite song. We’re looking at the visual manifestation of study and passion blended into the writing to convey information and feeling at the same time, and done so effectively. This is what writing what you love looks like.

There is MUCH more we have to learn from Tomi Adeyemi.

If you want to learn more from Tomi Adeyemi, listen to her, not me. She has a website/blog that shares all sorts of useful information for writers. I recommend everyone, even if you don’t write Fantasy, read and watch her blog. I can’t emphasize enough how amazing she is as a writer and as a community leader.

Educated by Tara Westover. Memoir.

See here for The Atlantic’s review of Educated.

Chapter 1 Number of Pages: 9

Number of Scenes: 2

Number of “Moments”: 3

Number of Lines of Narrative Summary: 118/295

Number of Lines of Interiority: 97/295

Number of Lines of Foreground: 0/295

Number of Lines of Background: 295/295

Number of Lines of Action: 128/295

Chapter Tagline: Tara’s grandmother offers to take her to Arizona so that she can start school, against her father’s religious-extremism that has kept all of her siblings at home, away from school, off the grid, in rural Idaho.

I’m going to be honest with you all: I have problems with this book.

Not because the writing is poor (it isn’t.) Not because the story isn’t engaging or powerful (it is.) And not because it comes from a bad place (I don’t believe it does.) I have problems with this book because, well, I’ll refer to Micki Mcelya in her piece “The Education of an Ambivalent Feminist”,

“Like everything else in her memoir, Westover’s education rejects analyzing the collective conditions of women, their diversity and intersectional oppressions across time and global geographies, activism and political change, or social justice. She sees little beyond her own experience, knowledge, and the freedom of her choices—sheared as they are of their foundations in the abiding privileges of her whiteness and Americanness and in the very same feminist texts and activism she describes rejecting.”

This being said, Educated is a #1 New York times Bestseller, was one of President Barack Obama’s favorite reads of 2018, won the Goodreads Choice Award for Memoir & Autobiography, was a finalist for several National Book Critic Circle’s awards, and is currently listed at #9 in Amazon’s Best Sellers Rank. This is an extremely popular book, regardless of how I feel. So, I’d like to explore what made the first chapter of this immensely popular book successful, and how writers can learn from it. But, I forewarn you, my lessons that I gain from this specific case study may more be based on what we, as writers should do better than what Tara Westover did right in her book Educated.

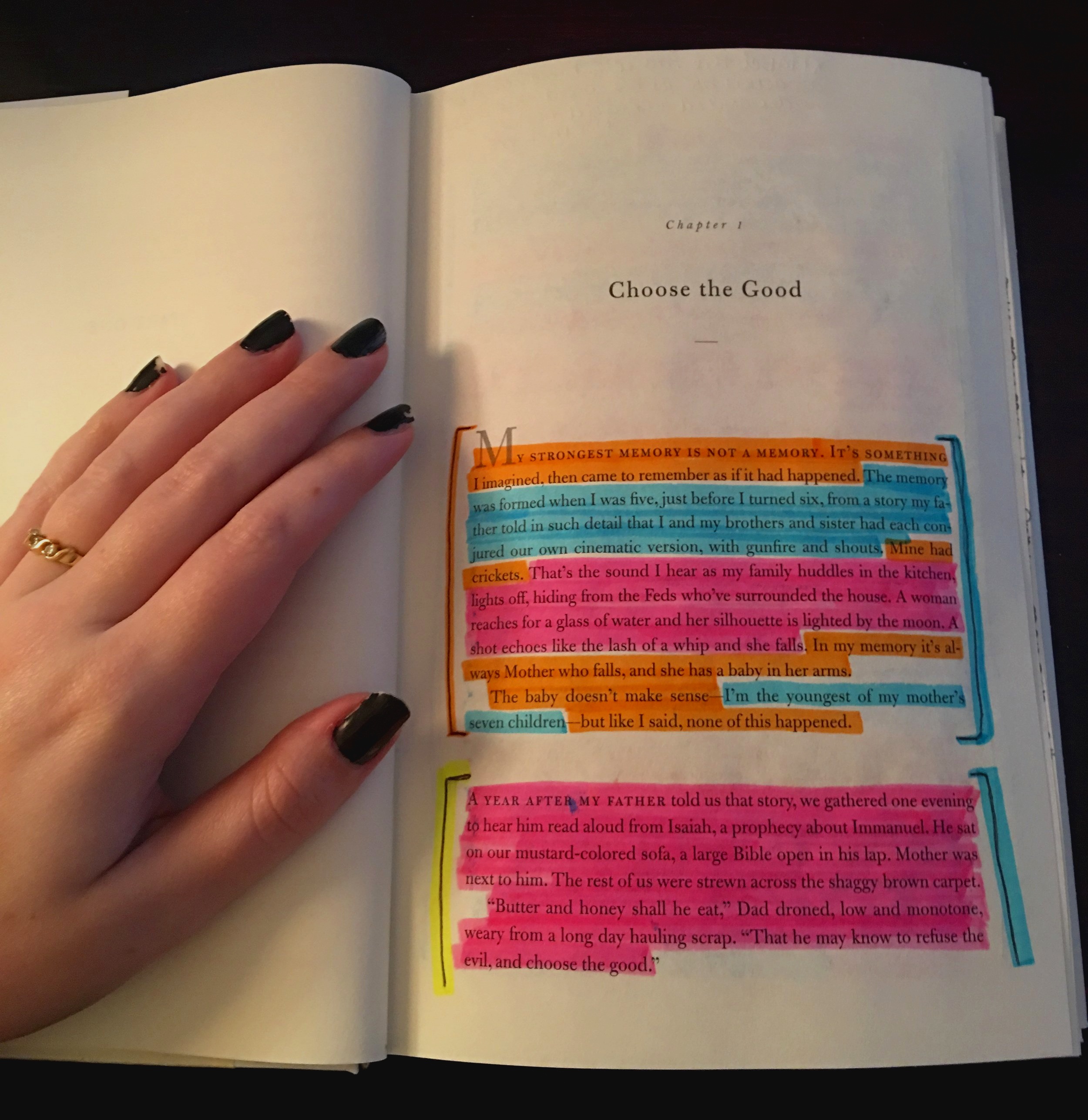

The first thing I noticed about the first chapter of Educated is that the lines of action (classified thus) don’t feel like action. It all feels like interiority, but it isn’t. The first sentence of chapter 1 is interiority, specifically reflection,

“My strongest memory is not a memory.”

The choice to have the first sentence be interior makes clear, logical sense. This is the nature of memoir. Reflection. But after that, throughout the rest of the chapter, I continued to notice that action felt more like interiority. And I only really noticed this when I started going through the annotation process. And I believe this thing I noticed is worth discussing because it draws on expectations/assumptions/conditioning around what is active versus what is passive.

The term “action” perhaps has come to mean something in our minds today that doesn’t lend to its definition in writing. “Action” connotes fast movement, shoot outs, fights, sports, passion— motion in all its forms. But one line of action I read on the second page of Educated reads, “We sat quietly.” This sounds passive. But it is an action in and of itself. To sit, to be quiet, those are choices made; they are an action. This feels quite different compared to the book I read immediately before— Children of Blood and Bone— where action tends to fit within the definition we picture in our minds. Memoir challenges our definitions of things we read, especially when we tend to read fiction over non-fiction. When the medium is based on reflection and commentary (interiority,) it bleeds through, masking action.

I have tried to pinpoint where, on the page, the feeling of passive action comes from. I wonder if it comes from the fact that memoir is a collection of memories— backstory—therefore there is a consistent use of the word “was.” This verb conjugation— a short, often ignored word— is a source of “passive voice.”

*Eye roll*

Passive voice versus active voice is a lesson most English writing students encounter at least 20 times in their educational careers. And, speaking for myself, I never once understood it. They were just words. Meaningless words that I dreaded seeing written in red on my papers. It didn’t make sense in real life.

Until today. Until really thinking about Educated’s structure.

According to Purdue University’s online handout about active vs passive voice, passive voice is when

“…the subject is acted upon; he or she receives the action expressed by the verb.”

Here is an example from that handout:

Active: The dog bit the boy.

Passive: The boy was bitten by the dog.

There’s that “was” again. But “was” is not the only sign of passive voice, nor is the use of “was” indicative of passivity. “Have” and other variations of “to be” can also constitute passive voice.

In writing school, and even before that, when I was in high school English classes, passive voice = bad. When I accidentally wrote a sentence in passive voice, my teachers would latch onto it with their red pens and would dock points. Those points added up fast. Passive voice became equivalent to “WRONG!” in my brain. But I’ve come to learn that not all passive voice is bad. Sometimes it is necessary and unavoidable.

So what’s the problem with passive voice? Why are we trained to avoid it?

According to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Writing Center, passive voice is not a grammatical error. It is a stylistic choice that can cause problems with clarity and impact. Essentially, passive voice makes it harder for a reader to understand what you are saying and passive voice makes your writing feel slower, less passionate, less excited, less impactful.

I am not saying that Educated is full of passive voice. What I am saying is that the writing makes the actions feel passive. And, partially due to how we are taught about passive voice and active voice, we tend to respond negatively to feelings of passivity on the page. As writers, this gut reaction is something we need to contend with.

I think this raises an important question for us writers: How can we challenge our language to combat the sound of passivity? Even in a genre like memoir, where the entire point is to reflect on the past, on what “was,” is it possible to make sentences feel active as they live in the past? Is there worth to that effort?

Yes, it is worth it. We must ensure that our language, no matter the genre we are writing within, is clear and strikes the reader in the way we wish.

Here is the First lesson we can learn from Educated’s first chapter: To combat passivity in our use of interiority, we must challenge the way we explore memories.

Memories, though in the past, can be retold to feel active. It all depends on the tone we want to set as writers and whether or not we are willing to do the work.

One choice Westover made throughout her first chapter in her retelling of memories that I deeply appreciated was her expert use of narrative summary. Overall, I found more narrative summary than interiority, which was a surprise because, as this is a memoir, I expected to find more interiority than narrative summary. How Westover wove narrative summary into interiority allowed for world building early on that I felt like I needed. How exactly did she structure these passages? At the beginning of a paragraph or section, Westover would lead with an interiority sentence, which would be proceeded by a longer passage of narrative summary. By supplanting “I remember blah blah blah” with "this is how it would normally be,” she combined reflections with information that we, the readers, need in order to understand the world of her childhood.

Here is a visual example (right.)

Let’s look around the center of the page at the section that begins, “I imagined what would happen…” highlighted in orange. This first sentence is interiority. She is reflecting on what she imagined would happen if she left Idaho with her grandmother, leaving her family unawares. The section that follows is all within her head. But I deemed pieces of this section as narrative summary because they are conveying information to us about the setting, about Tara’s day-to-day life with her siblings, and about the dangers of the mountain where she has grown up. All of this is important for us to know so to understand her childhood experiences, which is the point of the memoir.

It would have been incredibly easy for Westover to have instead written: “I imagined what would have happened when my family discovered I was missing. My mom would have been terrified. My dad would have been disappointed. My siblings would have worried.” The end. But she went beyond that to summarize the experience of them searching for her, thus giving us much needed details of her life (highlighted in blue.)

But, while this tactic I find wise and economical, it raises another question I had while reading this first chapter. How do we define entire passages of imagined occurrences?

Many of Westover’s sentences of interiority in the first chapter of Educated begin with “I imagined…” A lot of this chapter is stuff that never happened. In fact, Westover begins the chapter by describing a memory that never happened— a memory that she fabricated from a story told to her by her father. I began to question this when I was trying to figure out whether to label those section as foreground or backstory. I decided to label them as backstory, just by following the logic that this is a memoir. But I struggled with this intellectually. Because these are imagined, are they without time? However, she is remembering the time she imagined this, which again tells me that this is backstory because it happened “then,” in the past.

The stumbling over this question led me to ask another: Is this the best use of space?

When it comes to first chapters, space is valuable. Is reflecting on memories that didn’t really happen the best use of time and space?

From a writer’s point of view, yes. If the imagined scenario is important to the big decisions of the character, then yes, that space is being used effectively. But I could easily see an editor or a publisher trying to cut that part of the text.

Here is our second lesson we can learn from Educated’s first chapter: Follow the needs of your character, even if it makes people question your use of space.

While I have problems with the politics of this text and its author, I still think the lessons learned in its first chapter are valuable for new writers to hear. We must recognize the genre/industry structures we are forced to operate within, without letting them stifle our story and voice. We have to follow our guts, but we also have to know when to challenge our tendency towards laziness.

Neverworld Wake by Marisha Pessl. YOung Adult + mystery.

Here is a review from Barnes & Noble’s BNTeenBlog, written by Melissa Albert. If you prefer to watch, here is a vlog review by Alex Black.

Chapter 1 Number of Pages: 11

Number of Scenes: 1

Number of “Moments”: 16

Number of Lines of Narrative Summary: 112/287

Number of Lines of Interiority: 95/287

Number of Lines of Foreground: 120/287

Number of Lines of Background: 167/287

Number of Lines of Action: 89/287

Chapter Tagline: Beatrice is invited to her friend’s house for a birthday party, and she decides to go so she can reconnect with her friends, with whom she lost touch after the mysterious death of her boyfriend.

Neverworld Wake’s first chapter was incredibly difficult for me to annotate with this exercise, specifically with regards to time (scene vs scene fragment & foreground vs backstory.) Why? Time seemed to be absent from this first chapter. This, honestly, left me feeling at times very detached from the plot. Where I felt very connected to the story world, I was lost in time.

The book has been called by reviewers a “Groundhog Day plot,” which essentially means that, in one way or another, time stands still or moves strangely in this book. The point here is that my confusion with trying to assign timeliness to each moment was warranted. I wasn’t wrong and the book wasn’t wrong; the plot simply requires different rules of time to function.

Let’s explore that.

Scene fragments, or moments, tend to be flashes of memory containing information we need to understand the character’s feelings. Inherently, moments prioritize emotion. They stop time or they slow time down so that the narrator can cover the story or memory while the larger plot moves forward. Ergo, moments alter the time on the page— separating us from the time passing in the actual, diegetic story world— to show preference for certain feelings, reactions, and emotions over others. Imagine a two story building connected by an elevator. The top floor is the time on the page, closest to the reader. Time here can be sped up or slowed down as needed for the narrator to make a point. The bottom floor is the time in the story world, closest to the characters. The elevator is the narrator. The narrator can move outside of time as required.

Because the entire chapter is made up of moments, the narrator is continuously sliding around in time, prioritizing various feelings of the main character, which explains why I had a hard time knowing where in time I was (as the reader) at any given moment.

As I grappled with understanding the relationship between scene fragments and time in the narration, I started asking more questions than I had answers for.

This got me thinking: I don’t remember a single lesson or a class throughout my writing education that ever really discussed how to write time. We discussed pacing, but that isn’t the same thing as time. We discussed flashback and the importance of memories, but not in reference to structure. Even when we read science fiction or fantasy books where time can be bent and molded to the needs of the plot, we weren’t discussing the concept of time in the writing; we were only discussing time as a plot device.

What other fields study and debate time as a concept?

Physics is one.

In physics, time is a celebrity. Time is a figure present in numerous on-going discussions and theories about how our universe works. If you have seen the film Interstellar or if you have watched the documentary The Most Unknown, then you definitely have a picture of what I mean when I say that in scientific areas of study, time is openly debated, discussed, and explored— just like the ocean or space. If you would like a crash course on time, watch this really cool, but short Ted video.

The picking apart of time— scientifically and philosophically— has produced amazing ideas. Perhaps more importantly, it has produced amazing questions.

So why don’t writers— the big dreamers and imaginers of our species— debate time in our writing? Maybe some of you reading this have had discussions in the classroom or in community events about structuring time in your writing. If you have, please share with me what you learned. I’d love to hear from you. But, if you’re experience is like mine, and you have not yet encountered debates about time in writing, have you ever wondered why? I didn’t until I wrote this blog post.

So let’s do it here. Let’s explore time in Neverworld Wake’s first chapter. And, like scientists, we will need some sort of measuring tool to do this. That tool is structure.

We should start with scenes and scene fragments.

This was a chapter of moments; I could not discern any larger scenes present. The lack of definable scenes within the chapter, led me to believe that the entire first chapter, therefore, was one big scene, composed of scene fragments/moments.

On the left side of the pages pictured (right), you will see orange brackets spanning vertical sections. Each bracket holds a scene fragment/moment. The progression of plot is broken down into moments that connect different pieces of the main character’s life. How did I determine the span of each moment? I looked for a definable idea.

For example, the paragraph on page 12 (left page) that starts with, “Sudden Death of the Love of Your Life…” begins a new moment. It ends at “Except maybe The Exorcist.” The idea captured in that moment is that people need the comfort of categorizing death through different grieving processes, and our main character’s experience with death has placed her in a category where people don’t know what to do with her. Her boyfriend died and no one seems to know why or how. Therefore, they don’t know how to tell her to cope. Therefore they are uncomfortable around her. But frequently in Neverworld Wake’s first chapter, there were plenty of examples where it was not as clear-cut when a moment ended or began. I found myself making mistakes and going back in later with new interpretations.

The two pages here (left) show that clearly. The orange brackets on the left side of each page show where I changed my mind. Oftentimes writers will create new paragraphs with each scene fragment. But in Neverworld Wake, there was a moment that took me by surprise because it began towards the bottom of a paragraph (see sentence that begins, “I attended grief support group…”) In this moment, which ends half way down the next page, we explore Beatrice’s experience in that grief support group before she totally gave up on it.

Then, suddenly, there is a moment right after that where she explains how she taught Sleepy Sam to make grilled cheeses.

Then, at the bottom of the page, begins a new moment where Beatrice thinks about a dress she purchased but has never worn. She considers wearing it to her friend’s party.

After this brief moment, she reflects on the day of the party, leading up to her drive over.

The placement of information tells us a lot about priorities. The decision of when the narrator shares information tells us something about the importance of that information. Typically, we imagine important information being placed in strategic areas where the reader’s attention will be at its peak. Less important information can be placed in less visible spots.

With this logic, the arrangement of moments felt jumbled to me. I considered what I would have done differently. I would have closed the backstory spanning from page 6-7 with the moment about the grief counseling, since the story seems to be partially about her dealing with her boyfriend’s death, instead of sticking it in between a scene fragment about her work around her parents’ restaurant and a fragment about grilled cheeses/going to a separate party with Sleepy Sam. But then I chose to think under a different logic.

What if the writer placed information not based on the priority of the information to the reader, but rather based on the priority of the information to the world around the main character?

This makes the most sense to me when I think about the concept of grief, which plays a big role in this story. Most of society tends to believe that time heals all. But, as many of you may know well, time doesn’t heal all— especially grief. Those around us expect us to grieve on a timeline. It hurts the most right after the death and then it slowly gets better as the days and weeks pass. Although it isn’t really true, our grief is prioritized by time. The segmentation of details (organized into scene fragments) does not tell us much about how Beatrice prioritizes things. Rather it tells us about how she is prioritized in the larger world. We hear about her boyfriends’ death only after she reflects on how the owner of a local joint her parents frequent would react to her improvements since her grieving process began. How her neighbors study her and prioritize her needs/emotions is reflected in how the narrator (Beatrice) prioritizes information we become privy to.

Here comes the main lesson from Neverworld Wake’s introductory chapter: The physics of reality can and should be shaped to fit your story and your commentary on the world.

And it’s on us, the writers, to challenge our assumptions and restrictions to do so. Don’t let rules about what takes priority stop you from setting the tone and mechanics of your story universe. Its your world and your voice— let your structure amplify them.

To close this post, I’d like to quickly list the lessons learned from each of the texts here.

Set expectations in your first chapter.

If your story is one stemming from survival, use your words and style to spark debate and maybe even discomfort.

Don’t be afraid to wear your heart on your sleeve.

Write what you love.

To combat passivity, you must challenge the way you explore and re-tell memories.

Follow the needs of your character, even if it makes people question your use of space.

The physics of reality can and should be shaped to fit your story and your commentary on the world.

I know this was a long-winded post. I won’t linger here longer than necessary. I’d just like to finish by saying that if we want to be the best writers we can be, we must make time to study new writers and new books. They offer just as much as the classics. In fact, they might offer even more. It takes time to begin a conversation about a text that doesn’t have centuries of analysis and critical attention to lean on. But by doing so, we are expanding the conversation in bold, new directions. It’s on us to make conversations about books relevant. It’s on us to inspire new ways of thinking about readership. It’s on us to build the kind of literary community that we want to live in. I hope that this conversation we had here might inspire some of you to encourage your teachers, your friends, your writing coaches to think critically and meaningfully about new books and new writers. This is how we strive for change.