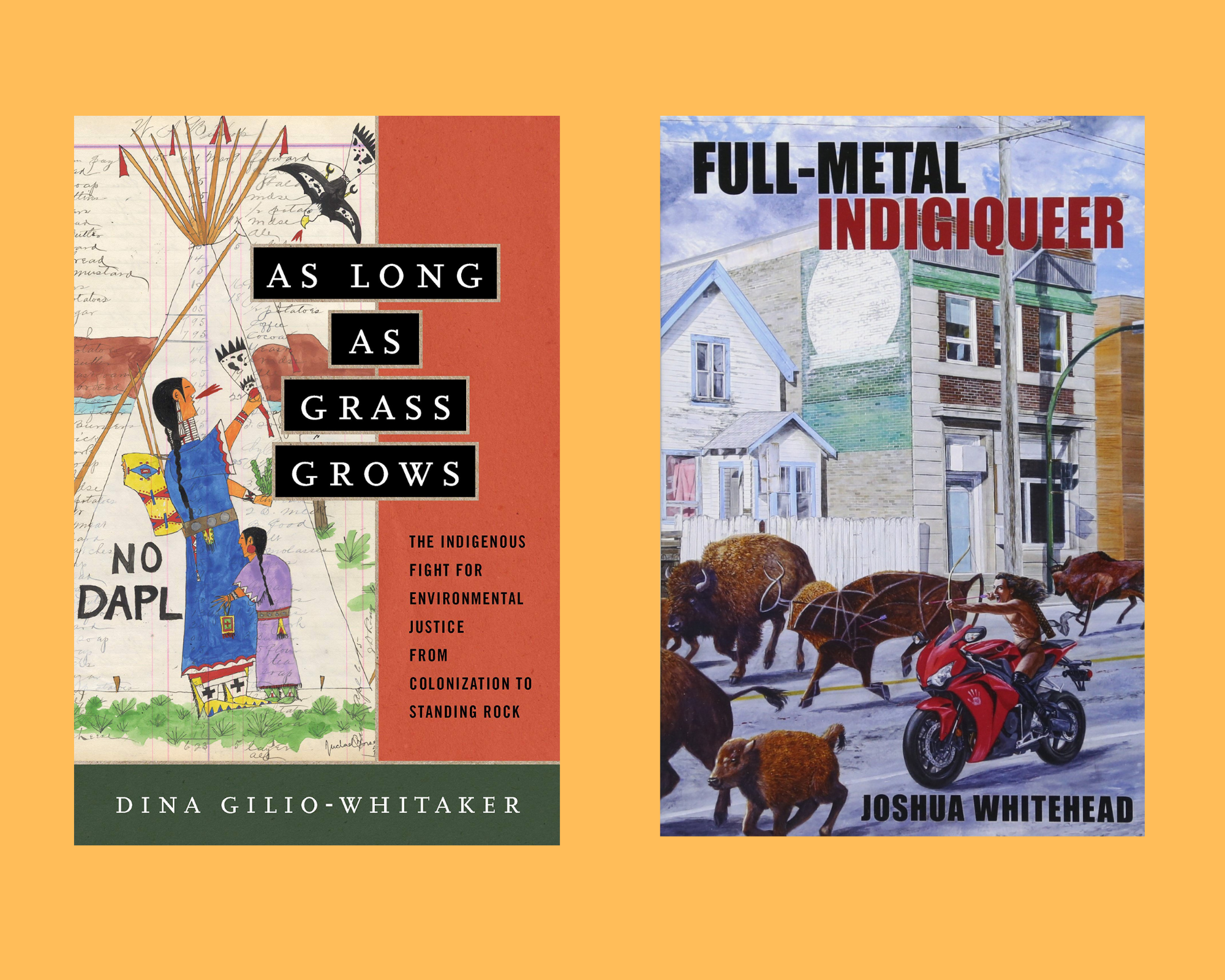

Commentary: As Long as Grass Grows + full-metal Indigiqueer

By Chava Possum

The Decolonize This Book Club read Dina-Gilio Whitaker’s As Long as Grass Grows: The Indigenous Fight for Environmental Justice, from Colonization to Standing Rock paired with Joshua Whitehead’s debut poetry collection called full-metal Indigiqueer for our June and July meetings. Together, the two texts ask the question: How do we save the world when the apocalypse has already happened?

Recently, I read Joshua Whitehead’s short story collection Love After the End: An Anthology of Two-Spirit & Indigiqueer Speculative Fiction which blew my mind because it clearly posits that, from Indigenous perspectives, the apocalypse has already happened; it started with European invasion and continues to this very day with the on-going violence against Mother Earth. full-metal Indigiqueer more so focuses on the colonized self and how constructions of identity are distorted, altered, ruptured, and reborn amidst colonization.

The poetry in full-metal Indigiqueer was difficult to read because it was written using binary code, meaning that the work of deciphering the words falls on the reader. But the decoding process itself is central to the reading experience as it suggests that consciousness questions identity, demanding a parsing out of the elements of self and where they originate and why they matter. We begin the collection with birth, code where there once was nothing. And as we progress, our host, a queer, Cree, NDN ghost in the machine discovers themself, interrogates the boundaries between I and we, and connects with histories of relatives, completing the circle from singularity to collective. Completion is the wrong word, as it suggests a satisfaction that comes with a sense of wholeness. Colonization in effect destroys “wholeness” as we feel it, as it separates people from land and from one another. The desire for wholeness weaves in with other desires, like togetherness, sex, ritual, place… even desire itself. We sense the ever-elusiveness of these desires as our coded host expresses anger, frustration, and grief in a dialect that is sarcastic and vulnerable at once. The desires of place and love tie together identities of Indigenousness and queerness, yet the dominance of whiteness, in queer spaces and out, has a habit of silencing and erasing Indigenous queerness.

Gwen Benaway writes in their review in Plenitude,

“Located inside Creeness, the sense of being dislocated from ancestral ways of being by violent colonial interventions, the speaker in full-metal indigiqueer alternates between interrogating the inherent whiteness of queer culture and mourning their particular longing for safe access to queer desire and community.”

“Indigenzing” can be a combatant against colonization, returning to Indigenous frameworks that never truly disappeared in the first place as a means of decolonizing ideas of identity, place, relationships, love, land, and yes, the apocalypse. Where the host in Whitehead’s collection is indigenizing themself, Dina-Gilio Whitaker’s book seeks to indigenize environmental justice.

Dina-Gilio Whitaker, member of the Colville Confederated Tribes and the policy director and a senior research associate at the Center for World Indigenous Studies, wrote As Long as Grass Grows to explore the Indigenous history behind the super-imposed environmentalist movement of the mainstream, questioning environmental justice and how it must be altered into its “indigenized” form to truly combat the effects that colonization has on the land and its people. She highlights the importance of building alliances across social and racial divides. “To do this,” she writes, “requires an honest interrogation of the history of the relationship between the environmental movement and Indian country.”

Using Standing Rock and the #NoDAPL resistance movement as a point of reference throughout the book, Whitaker leads us through the U.S’s history of colonization and genocide against the sovereign, Indigenous Nations who have long-standing, ancient relationships to this land and the sacred places dear to them for thousands of years. She examines the environmental movement, beginning as early as the preservation/conservation era with the founding of many of the U.S’s most famous National Parks and Forests and continuing through today in our current battle against climate change. And she goes back even further than that, taking us to the beginning of the apocalypse— European invasion. Over the course of this history, Whitaker ties inextricably together the numerous examples of biological warfare and environmental dispossession imposed by the settler State against the Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island to the fight for environmental justice, making clear that there is no justice for the environment when its Indigenous protectors and inhabitants are being killed and harmed by colonization.

As a white colonizer who turns to the term “environmentalist” out of convenience— I love and care about the land and want to do whatever it takes to protect it, so what else might I call myself?— Whitaker’s book was an essential read because it entirely reorganized my perspective on environmental justice and my role in nourishing/protecting the environment. No matter what I do or think as an individual, I am still standing in the legacy of colonization, benefitting from the displacement of Indigenous peoples and sitting comfortable thanks to extractive industries that poison Indigenous lands for profit. That’s uncomfortable. Naturally, my first reaction is to try to find a solution, a way I can “be helpful”. My thoughts turn to those who came before me, namely the hippie generation. But one of Whitaker’s most interesting chapters, in my opinion, was about that very generation of people and how even they participated in colonizing activities unintentionally as they sought out wisdom and knowledge about how to protect the land.

The back-to-the-land movement that the hippies are well-known for sought out answers to the critical questions around environmental degradation, coming from a genuine place of concern. But in this search, the hippies appropriated aesthetics of Indigenous peoples including long hair, headbands, moccasins, beads and feathers, leather and fringe, turquoise and silver. And then they inadvertently brought their Western worldviews into the reservations they visited and tried to warp Indigenous wisdoms to fit into Western frameworks, which in effect harms that Indigenous knowledge. Whitaker writes, “An orientation based on rugged individualism combined with a deeply ingrained sense of entitlement (Manifest Destiny in its modern form) translated into the toxic mimicry that today we call cultural appropriation."

There’s a lot to learn from this critical examination of a generation before my own, but it also reveals just how difficult decolonization work is even when it matters to you and you care deeply. So I turn to my own generation, the generation growing up amidst climate change and fear of the apocalypse. At first, all I feel is panic: what do I do? What can I do? The clock is ticking. And, like most white people, my perspective is limited to myself: my growth, my awakening, my journey. How does this impact me? Decolonization, however, requires a new relationship with ego, with me myself and I in that I am not singularly me; I am the accumulation of all who came before me. I am not separate. I am blended with everything else. And the I that I’ve cared so much about is only here to nourish the we. Does this mean I disappear? That I cease to exist? No. It’s just not about me.

The panic dissipates as I contemplate the apocalypse from Indigenous perspectives, the panic dissipates. It’s already happened. It’s happening now. It’s not a matter of me or any other white person “saving the world”; it’s a matter of turning to Indigenous leadership, recognizing and addressing the history of colonization, respecting Indigenous sovereignty, and decolonizing my self in honor of the world that was and striving for the world after the apocalypse.