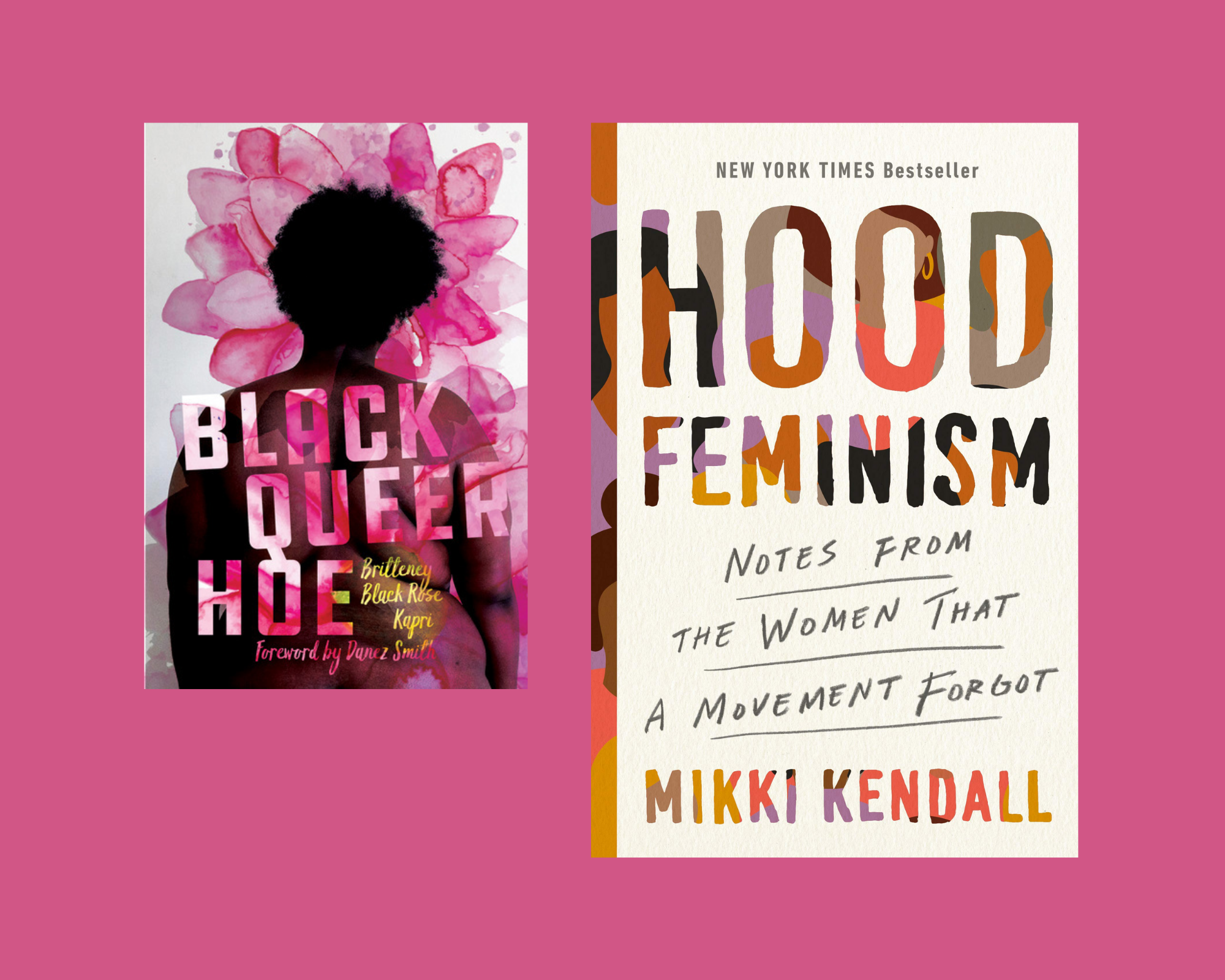

Commentary: “Hood Feminism” by Mikki Kendall + “Black Queer Hoe” by Britteny Black Rose Kapri

"... the hood taught me that feminism isn't just academic theory. It isn't a matter of saying the right words at the right time. Feminism is the work that you do, and the people you do it for who matter more than anything else."

Image by Chava Possum

Kicking off the second year of the Decolonize This Book Club, we chose Hood Feminism by Mikki Kendall and a collection of poetry by Britteny Black Rose Kapri called Black Queer Hoe. We intentionally paired these two texts, hopeful that their individual threads may occasionally lace together not out of sameness but rhyme. It’s like when you’re out with your best friend and they start playing yall’s favorite song; you hear the first notes and simultaneously grab hands in that burst of electric excitement: this is for us. Reading these two books together was like watching that magical dance: the blissful jam where all you hear is the music and all you feel is the ground beneath your fast-moving feet, then the lulls for drink breaks as the sweat chills you underneath the powerful A.C, then the swatting away of men like flies attracted to the sweetness of your step, then the bringing in of the other womxn who are eventually persuaded to take your hand and get lost in movement, until the song fades and the miracle of your body moving with hers carries you through the rest of the week.

Hood Feminism is a collection of essays by Mikki Kendall— a veteran, writer, speaker, and blogger— confronting the legacy and ideology of mainstream white feminism with an opposing framework designed to help one another, rather than one that emphasizes becoming a CEO. Kendall’s overarching point is that white feminism’s focus is on increasing white women’s privilege, at the expense of women of color. What Kendall calls “hood feminism” focuses on helping women get basic needs met. Her essays “Gun Violence”, “Hunger”, “Education”, and “Housing” all explore how women, particularly Black women, are uniquely marginalized in each sector, despite those topics not being considered traditional feminist issues.

“What does feminism have to do with guns? After all, guns aren’t a feminist issue, right? Except they are… many women, especially those from lower-income communities, face gun violence every day. The presence of a gun in a domestic violence situation makes it five times more likely that a woman will be killed. Women get killed by these guns because they are available, because their partners are violent, because an accident with a gun is more likely to be fatal…Although we tend to focus on the impact on young men who are exposed to gun violence, girls are likewise gravely affected.”

Each chapter, Kendall poses clear arguments as to why issues like gun violence are actually feminist issues and how feminism needs to evolve to meet those issues in real, tangible ways. (The only area I wish she had explored was the military. Because she is a veteran and because she sporadically mentions the military throughout the book, I find this to be a peculiar omission.)

But I wonder if Kendall is actually asking mainstream feminism to change or if she is stating that REAL feminism already exists and white feminists can either get on board with that or stick with their performative version that serves only itself.

"Mainstream, white-centered feminism hasn't just failed women of color, it has failed white women."

At the end of each chapter, Kendall includes a paragraph summarizing what needs to take place to make sure women are getting their basic needs met. In these calls to action, I could see how mainstream white feminists reading might misinterpret them as pleas for help (a savior perspective). But, the way I read it, it sounded more like Kendall was sharing the hood feminism she knows from her everyday life growing up and living in Chicago. She is actually inviting us to become accomplices in her feminism.

"Accomplice feminists would actively and directly challenge white supremacist people, policies, institutions, and cultural norms. They would know they do not need to have the same stake in the fight to work with marginalized communities. They would put aside their egos and their needs to be centered in our struggles in favor of following our instructions, because they would internalize the reality that their privilege doesn't make them experts on our oppression. This style of feminism would [not] be performative, would not pay lip service to equality while sustaining and supporting those who actively work against it. Becoming an accomplice feminist is not simply semantic. Accomplices do not just talk about bigotry; they do something about it."

The “real” work is already happening, led mainly by Black and Brown womxn. Kendall’s calls to action are invitations into that intersectional labor not as white saviors or leaders, but as accomplices. The sensation is one of being called out, then called in.

A similar kind of intimacy is reflected in Black Queer Hoe.

In Black Queer Hoe’s forward, Danez Smith writes that Kapri’s poems pivot,

“… so quickly through complex webs of tone, while patterns lure us into being disarmed… Many of these poems talk back to several audiences: to men on Twitter, men on trains, people in the speaker’s bed, to white women, to family, to friends. The poet uses the address all through the collection both as an extension of love and an act of defense. Everyone gets called out or in, everyone gets shouted out or implicated. Whatever the energy, it’s Kapri’s time to sound off.”

Unlike Hood Feminism, Kapri’s calling in is not an invitation. Boundaries mark each poem— don’t fuck with this space, don’t fuck with me. In a poem titled, “a reading guide: for white people reading my book”, Kapri steps through the illusory veil between reader and writer (observer and object), looks you square in the eye, and tells you this is not that kind of book.

“embarrassing white

folks and fuckboys is

my american pastime. this book isn’t

an invitation. i am

not your therapist or here to validate

that one time you stood up to your grandpa by telling

him colored was

outdated. don’t applaud yourselves.

instead show a Black

woman you appreciate them. all we

want is reparations

and to be left the fuck alone

by you.”

Hand-in-hand, these two texts tell truths, celebrate Blackness and Queerness, demand justice, ARE justice, tell of pain, and live a sacred intimacy. After reading Kapri’s final poem, holding the book to my chest, I felt more than anything gratitude. What a blessing to be here, to listen.

I’ll leave you with my favorite of Kapri’s poems called “haiku for reparations”:

“both these armrests mine

now. seat laid all the way back.

your comfort mine too.”