Commentary: Care Work + Kimiko Does Cancer

By Chava Possum

For the March Decolonize This Book Club, we read a collection of essays, Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha and Kimiko Does Cancer: A Graphic Memoir by Kimiko Tobimatsu.

Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha is a Lambda Literary Award winner, activist, performance artist, and writer who explains what disability justice is (and what it is not), the history of the movement (through personal stories and organizing examples), how WSCCAP (the white supremacist, capitalist, colonialist, ableist, patriarchy) impacts the experience of disability, turning the natural fact that we all live in different bodies and minds with our own unique skills, wisdom, and perspectives into a politicized human rights clusterfuck, where some bodies are valued for their productivity where others are de-valued for “lack of productivity”.

Then she explores how “crips” (as she self-identifies, re-claiming a word that has been used to dehumanize disabled people) navigate ableist society, including care webs: networks of neighbors and community members that give AND receive care, according to their ability, skills, and capacity. She lays out a system whereby disabled people give and take, where they self-determine what they want and need, rather than accepting whatever ableist caregivers decide they need, and where the skills they have had to learn to survive can be utilized to support others, rather than relying on oppressive systems alone for assistance. It’s mutual aid in a nutshell, designed by and for “crips”. Piepzna-Samarasinha doesn’t shy away from the politics of caregiving. Care is gendered and racialized. Women and femmes, particularly of color, are the ones expected to provide incessant care work at their own expense. Often with little to no pay or with little outside support. Care Work describes a movement that sees that fact, that directly addresses it, and that works to create paradigms where care is reciprocal, consensual, and that pull from “crip” knowledge and wisdom.

If you don’t know what disability justice is, don’t worry; I didn’t really know what it was either.

“Disability justice is a term coined by the Black, brown, queer, and trans members of the original Disability Justice Collective, founded in 2005 by Patty Berne, Mia Mingus, Leroy Moore, Eli Clare, and Sebastian Margaret.”

Throughout Care Work, Piezna-Samarasinha centers the role that Black and Brown, queer and trans leaders, activists, and community members had in the creation of the disability justice movement. You hear the fear in her voice, contemplating the present fact that many don’t recognize or respect the labor, ideas, and love of the movement’s Black and Brown founders. White-washing is everywhere including in Kimiko Does Cancer, a graphic memoir about a young, mixed-race, queer woman diagnosed with breast cancer and, specifically, the experience of the “after” of treatment.

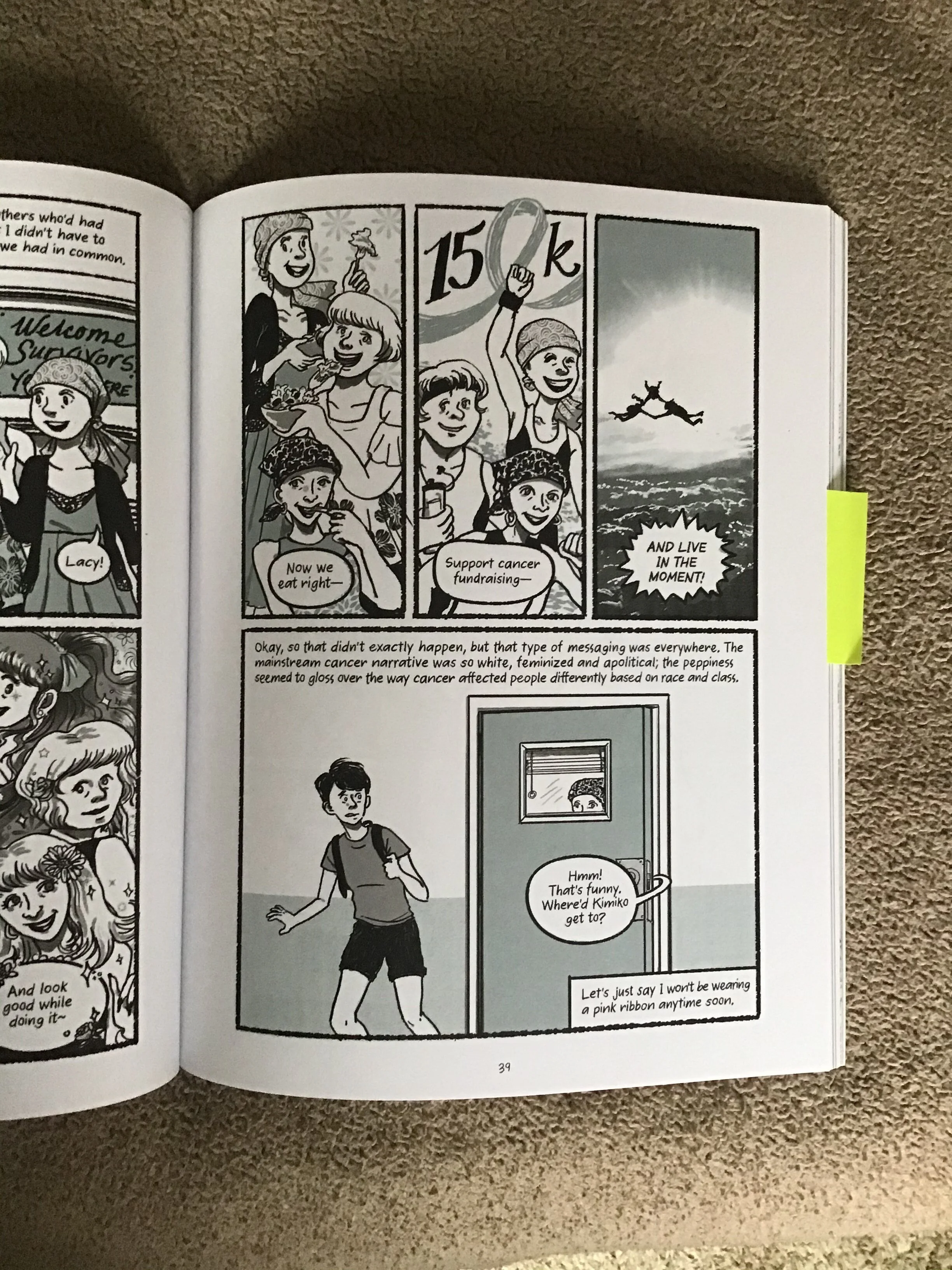

In the panels below, we see Kimiko meeting other breast cancer survivors, all of whom are white, cis women. Kimiko wants connection with survivors, to share space with those who get it, but sometimes it could feel like cancer was all they had in common. In the end, Kimiko writes,

“The mainstream cancer narrative was so white, feminized, and apolitical; the peppiness seemed to gloss over the way cancer affected people differently based on race and class.”

What’s it like to go through breast cancer treatment as a queer woman? As someone with boobs who is non-binary and queer, I have a unique relationship with my breasts that aren’t in alignment with the relationship most straight, cis women have. And that’s okay! What isn’t okay are health care systems or communities that expect or demand all women to share the same feelings about their bodies.

What’s it like to be working-class while on treatment for breast cancer? For the wealthy white women who survive breast cancer, making it to work on time, getting everything done, and somehow navigating the awkward body changes in the workplace aren’t as big of concerns as for working-class women who have to go to work. Kimiko shares her experience while working at a largely white law firm and how her treatment-induced menopause, which caused heat flashes and sweating uncontrollably, while at work… surrounded by men. Not the same experience as someone who doesn’t have to work.

And what’s it like to be a non-white person seeking treatment for breast cancer? When white bodies are the standard, bodies of color don’t receive the same quality of care. Not to mention being tokenized by studies.

All of these various identities intersect in Kimiko’s life and body. While we are inundated with survivor stories from white, cis, straight, and Christian survivors (though their stories are absolutely important), we don’t hear from survivors of color, who are queer or trans, working-class, and perhaps of a differing worldview than Christianity’s. Care Work emphasizes this as well.

Together, Care Work and Kimiko Does Cancer radically shifted my understanding of disability and disability justice and I heard similar sentiments from members of the book club. Seek them out!